Preserving West Tisbury – Sustaining an Island Community

Town Meeting adopts bylaw to limit impact and scale of new development

With last year’s overwhelming vote in support of what was commonly called the “Big House Bylaw,” West Tisbury became the third Island town to place limits on house size, joining Chilmark (who passed a similar measure at Town Meeting 2013), and Aquinnah (who added a requirement to review large house projects under the authority of the townwide District of Critical Planning Concern established by the MVC in 2000). Similar to those previous campaigns, the movement in West Tisbury came in response to the increased speed and scale of development in recent years, threatening natural resources and the rural character of the town.

Why Regulate House Size?

It is important to acknowledge at the outset that the increasing size of houses is only one aspect of the booming growth underway in West Tisbury and across the Island—and not necessarily the most impactful. It’s the total number of new projects that is primarily driving both seasonal and year-round population growth (though bigger size does increase a house’s short-term rental occupancy potential, a non-trivial consideration at a time when we are all carefully counting our nitrogen budget). So then, the opening question must be, “Why do we care about house size?”

First, larger houses have an outsized impact on the land upon which they are built. This can be very literal, in the sense of the amount of grading done to alter the landform—or when soil is exchanged as fill is trucked out during excavation, and then trucked back in again for landscaping after completion. Larger footprints require more clearing, increasing impacts to habitat (which in turn increases the project’s impact on groundwater and pond health, due to the importance of functional ecosystems in cleaning the water). And while it is not always the case, most often larger houses come with larger lawns, and larger—and more numerous—accessories, like pools, tennis courts, outbuildings, and parking areas.

Second, there is the effect overlarge houses and sprawling estates have on the affordability of living in town, and the risk this poses to the character and community of the Island. Just as we do when advocating for environmental protection, we should ask ourselves if we are selling the prospects of future generations for today’s profits in this sense as well.

Finally, we should consider the impacts of our decisions that occur outside our own backyard. The “embedded carbon,” i.e. the resources consumed in terms of the materials themselves (wood, concrete, steel, glass, and stone), plus the energy used by trucking them in from across the country (or world), is entirely dependent on the size of the house. Energy efficiency (or even zero-net-energy) helps mitigate the climate impact going forward, but—to be blunt—a big house has a big carbon footprint, period. The trend toward larger and larger house sizes is the wrong direction for an Island rightfully concerned about climate change.

Preserve West Tisbury

The West Tisbury campaign began when resident Harriet Bernstein gathered a group of like-minded community members, including Samantha Look, VCS Advocacy and Education director. Sam brought the VCS perspective to the group and facilitated our ability to put our full support toward the effort. The informal group of community activists ultimately evolved into a subcommittee of the West Tisbury Planning Board, taking on the name “Preserve West Tisbury.”

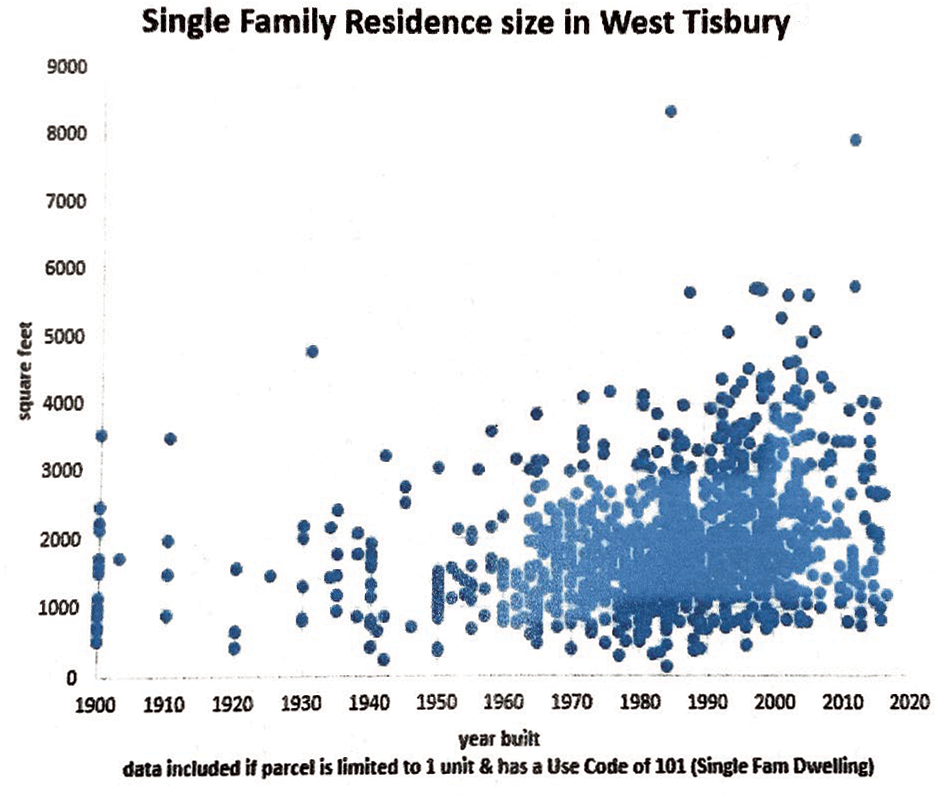

Preserve West Tisbury (PWT) began their work with information gathering: listening to other residents, consulting builders and engineers, and collecting data. The anecdotal feedback and the number crunching agreed: this was a community growing at an incredible rate, with a clear trend toward increasing house size. For most of the last century, house sizes clustered from 1,500–2,500 sq ft, with a handful of outliers around 3,500 sq ft. But toward the end of the century, houses between 3,000 and 6,000 sq ft became much more common—and the outliers grew to 8,000 sq ft or more.

The next task for PWT was to define more exactly what they hoped to accomplish. Broadly, everyone agreed that the goal was to establish both meaningful limits and a well-defined, objective review process to assess projects in terms of their environmental impact, as well as scale, proportion, and relationship to the existing community. But the group quickly discovered that achieving those goals would require regulations that were extremely granular, encompassing more than a simple limit on the square footage of one building. This in turn would require significant study of the Town’s existing zoning bylaws and relevant definitions.

The questions arising from that process were many. What do we make of accessory buildings? Which ones constitute living space and which don’t, and should either or both count towards the total allowed size? Do porches count? (Does it matter if they’re screened in?) What about basements—is it just “more house,” or is it an efficient use of space that should be encouraged? Should living space be measured on the inside or outside of the building? (It’s a seemingly trivial question, but important: measuring the outside is standard, and directly reflects the visual impact, but also acts as a disincentive to using thicker, energy saving, walls.)

Overall, the task was to effectively capture those projects that are truly excessive while not preventing a growing family’s ability to add bedrooms. But what is the magic number? How big is “big enough”—and by whose measuring stick? That is where PWT returned to the data, noting that despite the rising slope of mean house size, the more typical house was still coming in under 2,200 sq ft. The topline numbers that emerged ended up very similar to those adopted by Chilmark: a limit of 3,500 sq ft on a 3-acre lot, with proportional increases in building size with lot size. Those numbers allowed for some growth in the average house size while arresting the worrying trend of “leapfrogging” the previous splashy build. Most current projects would still be allowed under the new rules, but today’s outliers would not become tomorrow’s norm.

A Resounding Message

While the new rules will have a direct effect by preventing—or scaling back—certain proposals, the more powerful impact may come from the message it sends: a clear statement, amplified by the resounding vote at Town Meeting, of the values held by the community. People come from all over the world to build homes on Martha’s Vineyard, and without a formal declaration of those values, spelled out in our bylaws, it’s not realistic to expect that everyone will instinctively absorb them.

No one wants our Island to become just another previously-unique East Coast tourist destination. But, to avoid that outcome, we must articulate a clear alternative. The sum of our decisions as a community determines whether we protect biodiversity and ecological integrity, and the Island’s scenic beauty and quality of life. Change is all around us; we must be agents of that change, not mere spectators.